Web3 Gaming History: From CryptoKitties to Mass-Market Adoption

|

|

Web3 gaming tries to tackle an old problem: who really owns digital items, and can players use them on their own terms? In traditional free-to-play games, all control stays with the publisher: items live on the server, and trading rules can change at any moment. Blockchain offers a different setup: each sword, plot of land, or card exists in a public ledger, with ownership and transactions secured by smart contracts.

But long before the talk of AAA metaverses, the space went through years of trial and error: prototypes, dead ends, and, sometimes, quiet breakthroughs. To understand how Web3 games came to be, we need to look back: from the earliest blockchain experiments to the introduction of ERC-721 (NFTs) and the moment CryptoKitties brought the concept of digital ownership into the mainstream.

Beginning of Web3 Gaming: Collectibles and On-chain Gameplay

The earliest attempts to connect games and blockchain came before Web3 was even a term. In December 2013, Rare Pepe Cards appeared on the Counterparty protocol, collectible meme cards traded over the Bitcoin network. Each was a unique token, but minting and trading were clunky: fees were high, and there was no standard interface for developers.

In 2014, Huntercoin went further. A minimal MMO built entirely on a blockchain: players moved characters by sending transactions, and the game world was stored in a distributed ledger. When a player’s unit died, any uncollected coins were left on the map and could be picked up by others. It was part game, part mining experiment.

These projects showed that a game item could exist outside a studio’s servers. But they also ran into hard limits: low network speeds, no way to support unique assets, and tools too raw for most developers. Still, the core idea was in place: digital ownership didn’t have to depend on the publisher.

ERC-721: NFT Revolution

The introduction of Ethereum and the ERC-721 standard marked a practical turning point. Unlike fungible tokens (bitcoin, for example), ERC-721 allowed for individual tokens with unique IDs and metadata (now known as non-fungible tokens, or in short, NFTs), well-suited for representing specific game items.

This was first put into practice with CryptoKitties, released in December 2017. Each digital cat was tied to an ERC-721 token with a unique DNA hash. Some users paid tens of thousands of dollars for rare traits, and peer-to-peer trading quickly made the game widely used within the Ethereum ecosystem. But its popularity also exposed a major issue: the surge in transactions clogged the network, and gas fees jumped sharply, highlighting just how limited Ethereum’s scalability was at the time.

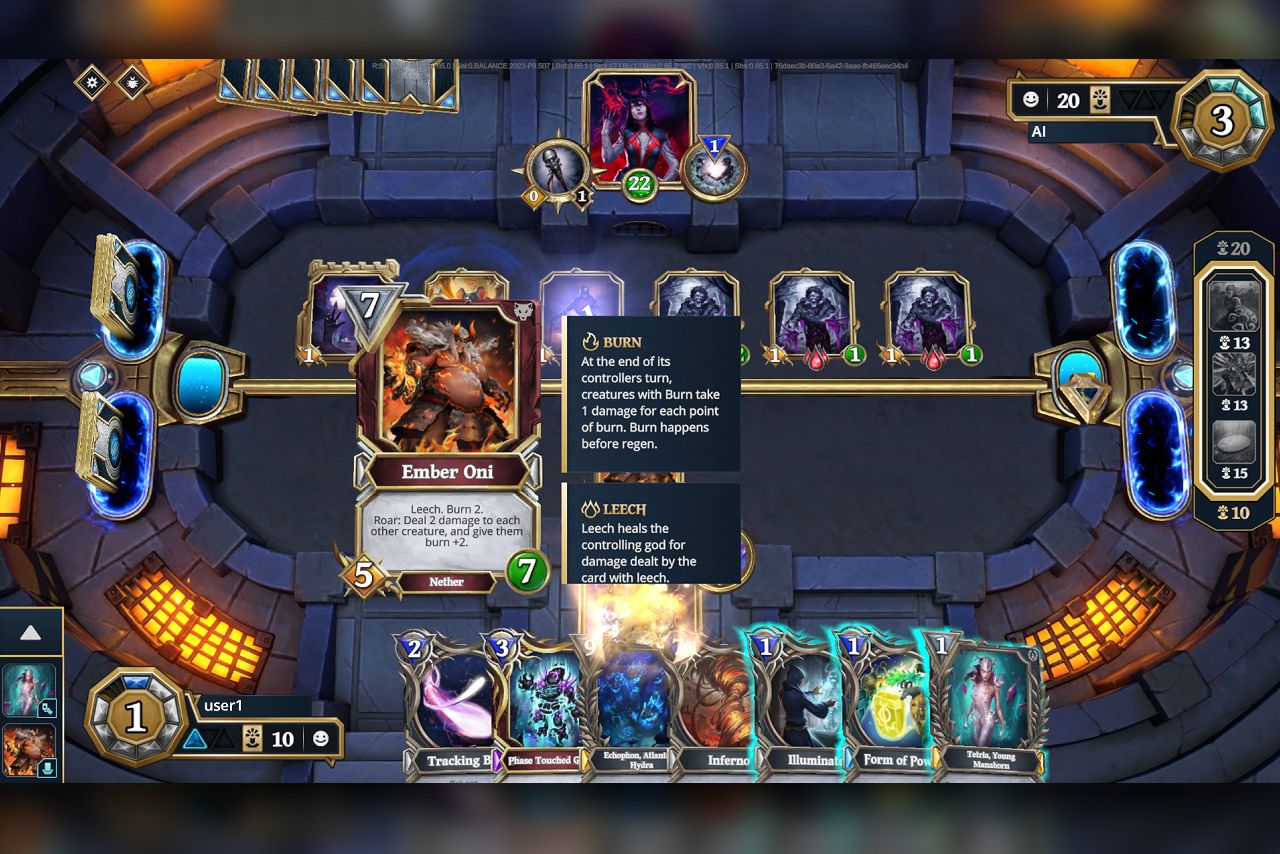

The real legacy of CryptoKitties wasn’t the cats—it was awareness. NFTs could serve not as a ticket to an ICO, but as core game assets, where value comes from rarity and user demand, not just speculative hype. Dozens of projects adopted ERC-721 soon after: from card games like Gods Unchained to early metaverse projects like Decentraland with tradable land NFTs. A new phase began, where developers started building gameplay around their own tokens, and for the first time, players could technically own in-game items without relying on a publisher’s infrastructure.

Gold Rush: Lessons from the ICO Boom

After the CryptoKitties boom, a wave of blockchain startups rushed to raise money through ICOs, promising a brand new future of gaming. Axie Infinity launched its alpha and began selling monster eggs, Gods Unchained raised $15 million through early card sales, and dozens of projects issued tokens without working gameplay. Investors were evaluating whitepapers, not game builds or actual gameplay, and the space quickly filled with half-finished clones: Decentraland’s Gaming District ICO led to abandoned zones, and MobileGo never delivered its promised marketplace.

At the same time, so-called on-chain mines appeared: basic decentralized applications (dApps) where users deposited ETH to mint new tokens and earn dividends from future participants. Once the inflow slowed, the structures collapsed, exposing them as unsustainable. The damage hit both investors and the credibility of Web3 gaming.

The period showed that a token, by itself, can spark only brief speculative interest. Long-term demand arises from engaging mechanics that keep players returning and spending time in-game. Without that core gameplay loop, even the most cleverly designed economy runs out of buyers and collapses under its own weight.

Rise of Play-to-Earn During Pandemic

By spring 2020, Axie Infinity relaunched on the Ronin sidechain with low fees and added a second in-game currency, SLP, effectively turning monster breeding into a form of work. The pandemic and lockdowns made the model appealing as a source of income: in some South American countries, thousands of families were earning more through Axie than from traditional jobs. This gave rise to loan guilds: organizations that bought up expensive Axie NFTs and loaned them to new players in exchange for a cut of the earnings. At its peak in mid-2021, SLP’s daily trading volume rivaled that of small-cap stocks, and Axie’s total market cap exceeded $9 billion.

But the rapid growth exposed cracks. SLP had no hard cap, and rising inflation eventually tanked the token’s value. In March 2022, a $620 million hack of the Ronin bridge revealed the risks of centralizing critical infrastructure. Around the same time, regulators began paying closer attention. The Philippine government debated taxing P2E earnings, and the U.S. SEC started asking whether some in-game tokens should be treated as securities. The lesson from this phase was simple: Play-to-Earn only works when new users keep joining faster than rewards are issued and cashed out.

GameFi Evolution: Owning Assets, Not Just Farming Rewards

In the downturn of 2022, many projects shifted focus from earning to owning. DeFi Kingdoms wrapped traditional farming mechanics in the skin of an RPG; Illuvium funded development by selling land NFTs with promised revenue shares; stepN brought tokenization into fitness with its move-to-earn model.

Games began adopting tools from DeFi 2.0: liquidity locks, dual-token systems, and token syncs to curb inflation. At the same time, many moved to Layer 2 (like Immutable X, Polygon) or alternative Layer 1 networks (such as Avalanche and Solana), cutting transaction fees to near-zero and making mobile support more practical.

The term “play-to-own” began to appear, shifting the emphasis from earning to enjoyment, with asset ownership treated as a bonus. It signaled a broader search for balance: developers started moving away from the pure P2E model and toward designs that prioritized the game itself.

Crypto Winter: From Collapse to Course Correction

After the collapse of P2E economies and the Ronin bridge hack, confidence in Web3 games dropped sharply. Major publishers began cleaning up platforms, distancing themselves from questionable token launches, while developers started moving from overloaded Ethereum L1 to cheaper alternatives like Polygon, Immutable X, and Solana, where transaction fees were negligible.

In parallel, regulation caught up. The EU approved MiCA, setting formal rules for crypto services and requiring stablecoin issuers to hold reserves (something that directly touched gaming tokens). The first licenses were granted in mid-2025. Immutable used the market reset to position itself as a trusted platform for studios. In 2024, it hosted 440 new projects—more than in all previous years combined.

Trust in pay-to-earn projects collapsed for both players and publishers, tarnishing the broader reputation of Web3 gaming. The industry needed a reset, so it began shifting toward play-to-own, a model that drops the constant token payouts, lowers financial and PR risk, and stands a better chance of appealing to audiences beyond the crypto community.

Web 2.5: Seamless Blockchain Beneath a Familiar UI

Most large platforms choose not to chase full decentralization. Instead, they made room for blockchain integrations without changing the user experience. The Epic Games Store dropped its commission on the first $1 million in sales, attracting indie teams and Web3 projects, while keeping wallets and gas fees hidden from view.

Ubisoft Quartz and Square Enix’s Symbiogenesis followed a similar path: NFTs exist in the background, but for the player, they appear as regular items in the inventory. Roblox is testing its own stablecoin and NFT-linked assets while scaling backend analytics to two trillion events per day, all with full control over the frontend.

Valve went in the opposite direction. In October 2021, Steam updated its developer guidelines to exclude any application built on blockchain technology that issues or allows the exchange of cryptocurrencies or NFTs. That blanket ban underscored how wary large mainstream storefronts remained, even as rivals like Epic began courting Web3 projects with more lenient terms. Well, some Web3 games still make it to Steam, as shown at Next Fest June 2025.

This Web 2.5 model lowers the barrier to entry for hundreds of millions of users, while keeping platforms in charge of access, moderation, and user experience.

Mass-Market Onboarding: Web3 Gaming Without Wallet

The backend of Web3 games has become cheaper and easier to work with. The ERC-6551 standard turns each NFT into its own wallet, letting one character or skin carry coins, power-ups, or cosmetics across multiple games without any extra inventory code.

Advances on the infrastructure side matter just as much. New zk-EVM roll-ups push transaction fees down to fractions of a cent, which finally makes on-chain actions practical for mobile players. At the same time, chain-agnostic toolkits such as Sequence or Unity Web3 wrap complex calls in simple REST endpoints, so studios can change networks or upgrade contracts without touching core game code.

By mid-2025, silent tokenization had become standard practice. Players log in through a social account, pick up items that are automatically routed to a custodial wallet, and never have to handle seed phrases. Creators still receive royalties straight from the contract, and assets stay live even if a studio’s servers go dark, removing the single point of failure that once defined traditional live-service games.

Challenges of Web3 Gaming

Economic fragility

A token economy lives or dies on fresh demand. Once daily sign-ups flatten, new coins or rewards pile up in player inventories faster than they exit the system, driving prices down and draining enthusiasm. A few whales cashing out can accelerate the spiral, leaving latecomers with assets no one wants and forcing studios to rebuild trust from scratch.

Legal uncertainty

MiCA lays out the broad rules for crypto assets in the EU (licensing, reserve backing for stablecoins, disclosure standards), but many of the enforcement details will arrive in staggered updates through 2026. Studios that operate globally must also track conflicting guidelines in the U.S., Asia, and emerging markets, updating terms of service and payout flows every time a regulator adds a new wrinkle.

User experience

Seed phrases, gas settings, and signature pop-ups still feel like command-line prompts to the average player. Wallet custody services help, yet every extra click or warning screen chips away at conversion. Full adoption will likely depend on invisible key management and gasless transactions that look no different from a normal in-game purchase.

Reputation

Early rug pulls and copy-paste projects taught players to associate Web3 games with risk rather than innovation. Established publishers have taken note; when Ubisoft slipped blockchain items into Captain Laserhawk, it did so quietly, avoiding big marketing claims. Until a polished, widely acclaimed release lands, many AAA publishers will keep their experiments low-key to avoid backlash from the gaming community.

Web3 Gaming: What’s Next

Interoperable assets

ERC-6551 reshapes an NFT into its own wallet, so a single token can carry coins, perks, or cosmetics to any game that agrees to read it. That removes the need for one-off import tools and lets developers treat inventory as portable rather than fenced in. The more studios adopt the standard, the closer we get to a genuine cross-game economy where a prized skin or mount is no longer trapped inside a single title’s servers.

Web 2.5 as the default

Epic, Roblox, and some other storefronts now run the blockchain layer quietly in the background. Players log in with the usual credentials and pay by card or wallet app, while ownership records and royalty splits are written to the chain out of sight. The platform still vets content and handles discovery, but creators see a clear revenue share instead of a flat one-off fee.

Player-owned identity and reputation

Attention is shifting from items to the profile itself. With token-linked accounts, achievements, rankings, and even disciplinary flags travel with a player from game to game. Studios gain a reliable reputation system without building new account silos, and players keep proof of their progress wherever they play.

Legal clarity

The EU’s MiCA framework and parallel bills in the United States are giving tokenized assets a clearer place in existing law. Mandatory reserve backing for stablecoins, licensing for exchanges, and standard disclosure rules reduce the chance that a game’s internal currency is later labelled a security and pulled from stores. As the patchwork of regional guidelines solidifies, both developers and players can worry less about a sudden regulatory rug-pull and focus on building or buying things that will still be legal tomorrow.

Web3 Gaming History Recap

Twenty-five years ago, players were creating hundreds of custom maps for Doom and StarCraft just from pure passion and for the thrill of seeing others play their work. Today, that same impulse fuels an economy where each new level, skin, or mod can carry a price tag and a revenue stream. The question is different: how do we make sure that anything a player creates can instantly become an asset, one that earns them a fair share?

Web3 already provides the rails, but lasting success will come only when three conditions are met. First, the economy has to be engineered for the long haul: token supplies must expand no faster than their real utility, sinks for excess currency need to be built into everyday play, and governance rules have to make it hard for early investors to drain liquidity overnight. Second, the interface must feel no heavier than a standard store checkout. That means social log-ins that spin up custodial wallets in the background, gas fees paid from a pooled account instead of the player’s pocket, and one-click refunds when a purchase goes wrong. Third, the legal ground has to stop shifting. Frameworks need to settle questions about asset classification, royalties, and consumer protection so studios aren’t forced to rewrite terms of service every quarter.

If those pieces line up, tokenization will fade into the scenery—another background service alongside leaderboards or cloud saves. At that point, the old argument about whether games should be fun or work loses its edge: players who just want to play can ignore the ledger entirely, while creators and collectors who care about ownership and earnings can lean into it, all inside the same world.