From Map Editors to Metaverse: Web3 on Monetizing UGC in Games

|

|

User-generated content (UGC) has always been part of video-game culture, from the first custom maps in Doom and StarCraft to today’s multi-million-dollar creator marketplaces in Roblox. Over the past three decades, falling technical barriers have widened the pool of creators from a handful of hobbyists to millions of player-developers, and with that growth has come a new demand: fair monetisation of their work.

The latest step in that story is Web3, which aims to lock ownership rights into smart contracts, turning mods, skins, and even virtual land into tradeable assets. How did we move from free custom maps to NFTs that sell for six figures, and why is “Who owns the players’ ideas?” still a question?

Anyone with a creative spark can now double as a micro-entrepreneur, blurring the old line between modder and developer. This article traces that journey from the first modding communities to today’s blockchain-backed platforms.

Modding’s Dawn (1990s-2000s)

When 3D first-person shooters were new and real-time strategy games on the rise, many studios opened up their toolkits. Id Software shipped map editors for Doom and Quake, Bungie—for Marathon Infinity (not to be confused with the new Marathon extraction shooter), while Blizzard followed with the World Editor for Warcraft III. Modders worked purely out of enthusiasm: Team Fortress, Counter-Strike, Aeon of Strife, and Defense of the Ancients were night-time passion projects, modders built them for recognition on forums or LAN bragging rights.

Legal ownership stayed with the publisher; licence agreements classed every mod as a derivative work. No one earned directly from these creations, but the portfolio boost was real—the Counter-Strike team joined Valve, and IceFrog went on to lead Dota 2. The legal landscape, meanwhile, was vague at best: donations trickled in through PayPal, and the most tangible reward was a studio job offer for the lucky few.

Formal marketplaces didn’t yet exist, so distribution happened through fan sites, magazine cover disks (the coolest thing I ever discovered this way was the Equilibrium movie modification for Max Payne 2), and word of mouth. The absence of direct cash flow kept the scene collaborative, but it also set the stage for future debates about who should profit when a hobby project becomes a phenomenon.

Modding for Profit: Steam Workshops and Skin Markets

As digital storefronts replaced boxed releases, modding began to look less like a hobby and more like a cottage industry. Steam’s arrival put an end to manual archive downloads, and by 2011, the Steam Workshop offered creators a built-in channel for sharing maps, texture packs, and total conversions. Visibility on the front page could drive tens of thousands of installations overnight, and for the first time, a single platform handled publishing, version control, and user feedback in one place.

Encouraged by that success, Bethesda tried in 2015 to add a price tag to Skyrim mods in Valve’s storefront. The backlash was immediate. Players objected that there was no clear revenue split, no guarantee of support, and no safeguard against plagiarized assets. Within a week, the experiment shut down, illustrating that a paid-mod ecosystem needed transparent accounting and active curation if it was to win community trust.

Meanwhile, a parallel market had formed around cosmetic items. Unusual hats in Team Fortress 2 and rare knives in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (now CS 2) were trading for four-figure sums on third-party websites. Value determined by player demand and not by any price the developer set. Those sales proved that virtual goods could carry real monetary weight even when they offered no gameplay advantage.

Markets outside of Valve’s ecosystem

Minecraft added another layer. Independent server owners began selling VIP ranks, exclusive skins, and custom mini-games. What started as a way to cover hosting costs quickly grew into dependable side income; a well-run server with a loyal player base could fund a small staff and continuous content updates.

Yet every one of these channels (Steam Workshop, third-party skin markets, private Minecraft servers) ultimately answered to a central authority. Valve or Mojang set the rules, skimmed a percentage, and retained the power to rework or close the marketplace at any time. That platform tax and the fragility it exposed, later drove both creators and players to look for ownership models that could survive even if the gatekeeper walked away—a search that cleared the path toward Web3.

YouTube and Streaming: Creators as New Economy

From the mid-2010s onward, media platforms became the main channel for monetising player-made content. YouTube, Twitch, TikTok, and Patreon let people who cut trailers, post let’s plays (nowadays, mostly forgotten format), or record guides and walkthroughs turn that work into a stable livelihood (if we don’t go into details about Adpocalypse). CPM advertising, sponsored segments, and paid communities replaced weekend hobby money with regular paychecks. In 2025, independent creators are projected to earn more from ads than legacy broadcasters for the first time. The broader creator economy now tops $191 billion and is expanding at roughly twenty-two percent a year, a pace that puts amateur productions at the centre of games-related media.

Yet final control still sat with the platforms. Recommendation algorithms throttled or amplified reach; unlicensed music or gameplay footage could trigger instant takedowns, as Nintendo’s mass copyright claims regularly showed. The underlying arrangement (you make content, we sell the ads) brought in revenue but left creators dependent on rules they did not write and could not challenge. That dependence pushed many to look for systems where asset ownership and distribution would be theirs rather than the platform’s, setting up the move toward decentralised models.

Decentralizing Game Assets: Web3 Gaming

Web3 gives a concrete answer to an old problem: who owns a digital object? Smart contracts can lock authorship and revenue splits directly into the blockchain; once the rules are in place, payments move straight to creators’ wallets with no middle layer to alter or delay them. Early proof came in 2017, when CryptoKitties showed that purely digital collectibles could fetch real money. In 2021, Axie Infinity went further, demonstrating that in-game NFTs could become a primary income source for entire communities during the pandemic. Fortnite added another data point: its Creator Economy 2.0 pool dedicates roughly 40 percent of item-shop revenue to island builders, and analysts note that a tokenised system could deliver the same benefit without relying on Epic’s internal metrics.

By 2024, both Unity and Epic had shipped official toolkits for blockchain plugins, and the first wave of Web 2.5 games reached mainstream stores. These titles hide tokens behind familiar menus; players log in as usual, never touch a wallet, yet still keep ownership of anything they earn or buy. The core idea stays the same: digital assets should remain the player’s property, even if the studio’s servers go dark.

Metaverse NFTs: How UGC Became a Revenue Stream

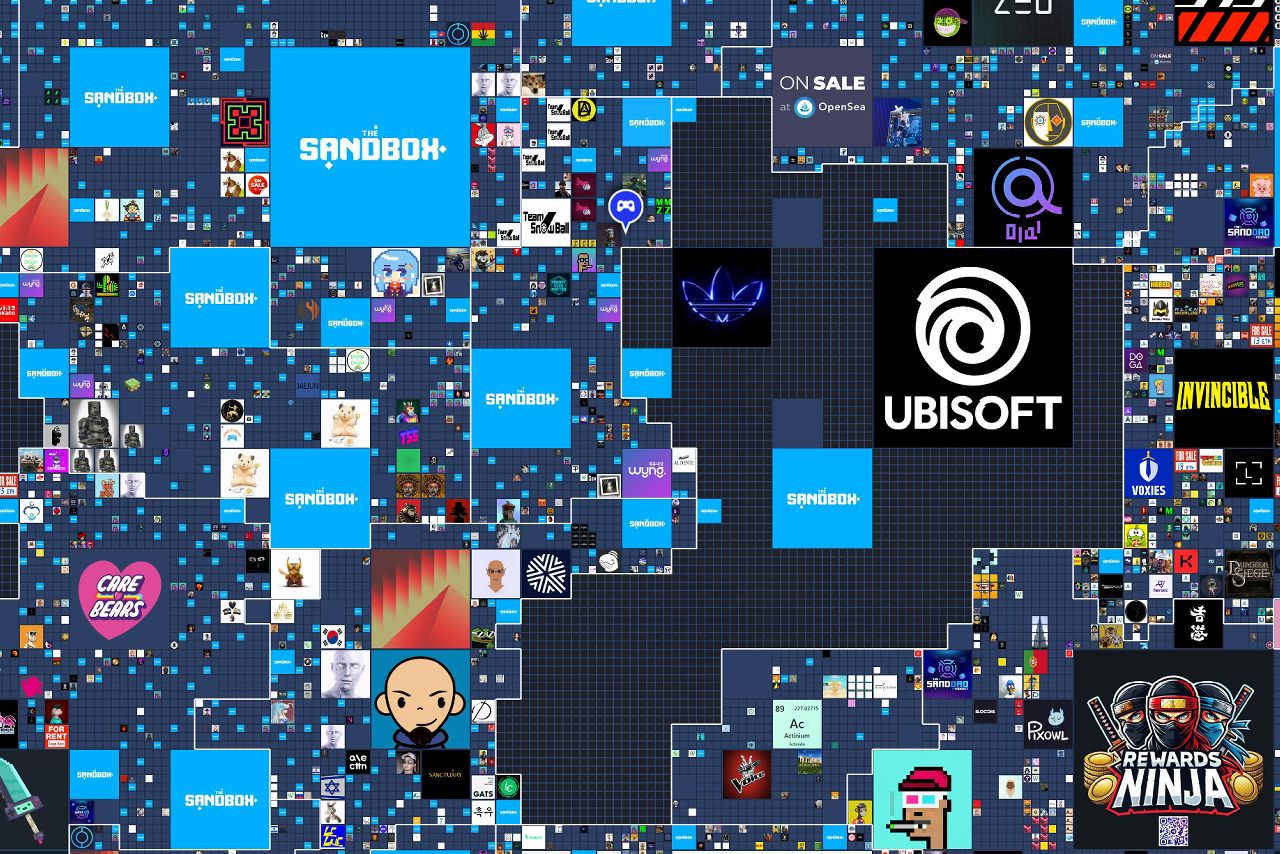

The next wave centres on fully player-built worlds. In The Sandbox and Decentraland, the development kit is open to everyone: upload a 3D model, mint it as an NFT, and each resale sends a royalty back to your wallet. Those steady trickles of commission have allowed the best teams to turn what began as art collectives into self-financing studios.

Market data confirm the model works, if only for a handful of projects. The Street counted just a few dozen Web3 games that were genuinely healthy by 2025, and all of them run on user-made content and on-chain markets where prices rise or fall on player demand rather than publisher policy. On OpenSea, the most trafficked listings are still virtual plots from Otherdeed, bundles of Sandbox land, and limited avatar drops from Wilder World.

The scene is nowhere near mass adoption: buying in can feel arcane, token prices swing wildly, and rug-pull scandals have shocked more than one community. Even so, a mental shift has already taken place. Creators now assume that every mod download, every resold skin, every square metre built with their assets will send something back to them, and the technology can keep that promise without a central gatekeeper.

Pressing Problems in Web3 Gaming

Turning game content into tradable assets sounds attractive, yet three persistent issues keep the Web3 economy from breaking into the mainstream.

Speculation and fraud

A flood of projects chased easy money, minting items whose only draw was artificial scarcity. As soon as attention moved on, prices collapsed and some developers disappeared with the proceeds, leaving players empty-handed after months of grinding. The most sophisticated scams now pose as long-term roadmaps, delaying payouts just long enough to avoid an early stampede for the exit.

Legal uncertainty

Owning an NFT does not automatically grant the copyright to its artwork or 3D model. The EU’s MiCA rules, which began rolling out in 2025, tackle stablecoin reserves and issuer transparency, but a full, globally consistent framework is still years away. Until then, studios must juggle a patchwork of national regulations, game-engine licences, and crypto-asset guidelines.

Entry barrier and user experience

Buying or minting an NFT still means setting up a wallet, guarding a seed phrase, and learning the basics of gas fees. Most players expect a two-click purchase, not a lesson in key management. Unless those steps disappear behind familiar log-in screens, Web3 gaming will remain a niche for users comfortable with crypto tooling.

Hybrid Models: Web 2.5 Balancing Control and Blockchain

With fully on-chain systems still hampered by high entry costs and regulatory uncertainty, leading platforms have settled on a halfway solution often dubbed Web 2.5. The blockchain layer stays out of sight, while familiar storefronts and logins handle the front-end experience.

Epic’s Fortnite illustrates the approach. In the game’s Creator Economy 2.0, forty per cent of item-shop revenue is placed in a monthly pool and paid out to island builders in proportion to actual player time. The mechanism is still run from Epic’s servers, yet the promise—automatic, usage-based royalties—mirrors what a smart contract would deliver. Epic is also testing its Fab marketplace, where external creators are to keep eighty-eight per cent of each sale. Separately, the Epic Games Store now charges no commission on a developer’s first one million dollars in revenue, removing most of the platform tax without requiring any blockchain integration at all.

Roblox is moving in the same direction, if more quietly. The company is piloting stablecoin-backed credits and game-specific tokens while keeping the crypto logic behind the curtain. Players purchase items as they always have; ownership is tracked in Roblox’s own ledger rather than a public chain. The set-up spares users the hassle of wallets and gas fees, yet still allows millions of builders to earn and cash out under a “play, create, own” ethos.

These hybrids preserve the advantages of a central platform (moderation, discoverability, working customer support) while automating a fairer share for creators. Web 2.5 could serve as an accessible bridge to fuller Web3 adoption. Even in the meantime, the shift is clear: more creators are being paid every time their work is used, and that share is increasingly viewed not as a perk but as a right.

Monetization as Baseline: What’s Next for UGC in Web3 Gaming

From the first Doom maps to virtual land in The Sandbox, one theme has never changed: players want a hand in shaping the worlds they inhabit. Web3 doesn’t invent that desire—it widens its reach by letting people create, keep, and profit from what they build. Tools remain rough, and plenty of projects still miss the mark, yet the mood has shifted. Players aren’t content to stay mere consumers; they expect a slice of the value their work creates. Ten years ago, sharing revenue with modders or skin artists seemed far-fetched. Today it is edging toward baseline practice.

That evolution points to a simple target: every asset should show its author, carry a traceable value, and include a mechanism for sharing revenue. Web 2 taught users to pay for convenience; the emerging Web 2.5 layer tries to add fair compensation without adding friction. The design task is delicate: reward creativity without turning every interaction into speculation. Hybrid setups (centralised interfaces paired with on-chain records) look like the most logical way forward.

The aim is to keep ownership and payouts out of sight for players who aren’t interested, yet fully accessible for those who are. If that balance is struck, the next generation of virtual worlds will expand not on hype, but on the tangible gains users find in creating things that endure.